12 February 2024

Women are much more likely to get autoimmune diseases than men. New research may finally explain why.

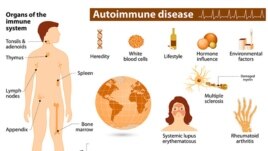

Autoimmune diseases happen when the body's natural defenses, or immune system, attack the body's tissues.

Researchers from Stanford University in California say the reason for this may be connected to how the body deals with females' second X chromosome.

Organs of the immune system. (Courtesy of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences)

The finding could help improve doctors' abilities to detect autoimmune diseases.

E. John Wherry is an immunologist at the University of Pennsylvania. He said the new study changes "the way we think about this whole process of autoimmunity."

Between 24 million and 50 million Americans suffer from an autoimmune disorder. Autoimmune disorders include lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and many other diseases.

About four of every five patients with an autoimmune disorder are women. Scientists have tried to find out why for many years.

One theory is that the X chromosome might be the reason. Females have two X chromosomes while males have one X and one Y.

The new research recently appeared in the publication Cell. The results show that the extra X is involved — but in an unexpected way.

Our DNA is carried inside each cell in 23 pairs of chromosomes, including the final pair that decides biological sex. The X chromosome is packed with hundreds of genes, far more than males' much smaller Y chromosome.

Every female cell must turn off one of its X chromosome copies to avoid getting a dangerous double amount of all those genes. Scientists call this process X-chromosome inactivation.

A special kind of RNA, called Xist, performs the X-chromosome inactivation. Xist is a long chain of RNA. It gathers in areas along a cell's extra X chromosome and attracts proteins that connect to it in unusual masses. Then it silences the chromosome.

Dr. Howard Chang is a dermatologist at Stanford University. He was exploring how Xist does its job when his lab found nearly 100 of those attached proteins. Chang saw that many of those proteins were related to skin-related autoimmune disorders. Patients can have "autoantibodies" that mistakenly attack these normal proteins.

Chang told The Associated Press, "That got us thinking: These are the known ones. What about the other proteins in Xist?"

He added that the molecule, found only in women, might "somehow organize proteins in such a way as to activate the immune system."

If true, Xist by itself could not cause autoimmune disease. If it did, all women would be affected. Scientists have long thought it takes a combination of some genes and an environmental event, like an infection or injury, for the immune system to cause problems. For example, the Epstein-Barr virus is linked to multiple sclerosis.

Chang receives financial support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which also supports The Associated Press' Health and Science Department.

Chang's team decided to produce male lab mice to artificially make Xist — without turning off their only X chromosome — and see what happened. Researchers also specially bred mice susceptible to developing a lupus-like condition. The condition can be set off by a certain chemical.

The Xist formed its usual protein masses. When the chemical was used, the male mice with Xist developed lupus-like autoimmunity at levels similar to females, the team found.

Chang said, "We think that's really important, for Xist RNA to leak out of the cell to where the immune system gets to see it."

But he added that an environmental event is still needed to start the process.

Beyond mice, researchers also looked at blood from 100 patients. They found autoantibodies targeting Xist-related proteins that scientists had not previously linked to autoimmune disorders. Chang said one possible reason was that most tests for autoimmunity were made using male cells.

More research is necessary. But Wherry, the immunologist at Penn, said the findings might give doctors a shorter path to diagnosing patients.

Wherry said one patient may have autoantibodies to Protein A and another patient may have autoantibodies to Proteins C and D. But he said knowing they are all related to Xist RNA can help doctors find diseases more easily.

I'm Gena Bennett. And I'm Gregory Stachel.

Lauran Neergaard reported this story for The Associated Press. Gregory Stachel adapted it for VOA Learning English.

_________________________________________________

Words in This Story

detect – v. to discover or notice the presence of (something that is hidden or hard to see, hear, taste, etc.)

dermatologist – n. the scientific study of the skin and its diseases

activate – v. to cause (a chemical reaction or natural process) to begin

susceptible – adj. easily affected, influenced, or harmed by something